THE BATALEON 20Y ANNIVERSARY BOOK

It’s big, it’s burly, it’s bursting at the seams with photos, graphics, stories and so much more! The 20Y Anniversary Book is a true collector’s item, 600+ pages covering the entirety of Bataleon’s history, including over 400 boards we’ve designed in the last two decades.

WRITTEN BY THOMAZ “TAG” AUTRAN GARCIA

Following section is the first chapters from the start to season 07/08.

BATALEON SNOWBOARDS

Early Years - Mid-90’s to 2004/2005

Produced at: GST

Director: Jørgen Karlsen

Contributing artists: John Harald Knutsson

Shapes by: Jørgen Karlsen

Team riders: Julian Karlsen (02-04), Christian Halland (02-04), Brett Butcher (03-04)

THE ORIGIN OF TRIPLE BASE TECHNOLOGY

It was a typical afternoon on a typical winter day in the early nineties in Norway. Typically for that time of year in that part of the world, the main TV station was broadcasting downhill skiing, a typical national pastime enjoyed by most —albeit not all— Norwegians.

A man called Jørgen Karlsen was watching the lycra-clad skiers hurtling down the mountain on his TV that day and while he looked and behaved mostly like your typical Norwegian, there was absolutely nothing typical about Jørgen’s brain.

As he observed the skiers leaning into turns on the screen, the edges of their skis lifting curtains of snow as they chattered and bounced through the race course, thoughts about motion, force, and wasted kinetic energy bounced around Jørgen’s mind, slowly percolating into an idea. Suddenly, a flash of insight, a burst of abrupt and triumphant comprehension! A wholly original idea, borne of a wholly original mind, finally crystalized and hardened into what is arguably the most revolutionary design concept in the history of snowboarding.

But we’ll get to that in a second.

Jørgen had always shown an avid interest in science, eventually going on to earn a degree in theoretical physics at university. However, whilst still working on his postgraduate degree he was hit with some life-altering news. Looming debt and illness threatened his father’s greenhouse business with rack and ruin, so Jørgen had no choice but to cut his studies short and take the reins of the family’s interest in order to save it from insolvency.

Despite his formal training being left incomplete and having to quickly adapt to a new reality of bringing a business that sold 30 million tulips per year back from the brink, Jørgen’s highly analytical mind continued to perceive the world in its own very unique way. Which brings us back to that fateful winter day in the early 90’s. Eager to take his mind off work after another demanding week, Jørgen watched silently as the racers made their way down the mountain. Despite his calm demeanor, his mind was working furiously on why the geometry of those skis made no sense whatsoever. With every turn the metal edges were digging in, causing the skis to plow through the snow instead of tracking cleanly through the arc, losing efficiency and bleeding off a ton of speed.

This was right around the time that Elan had begun making shaped skis —‘parabolic’ was the term they coined— that featured the innovative concept of sidecut, which of course would go on to become the new design paradigm for all skis. At this point, however, the majority of people still used stiff, straight-edged skis, especially in Norway where the country’s skiing legacy stretches back literally thousands of years, before recorded history even.

So Jørgen’s initial thought was ‘why aren’t they using sidecut’, but he knew that just adding sidecut wouldn’t reduce the amount of plowing and chatter, in fact sidecut actually resulted in skis vibrating at the tips uncontrollably once they reached a certain velocity. This got him thinking about how the torsional forces applied through turns were actually twisting the tips into a three-dimensional shape, lifting them off the snow.

If he could only figure out how to press a ski into a 3D outline that mimicked how it naturally behaved in a turn, that would create the ideal shape for maximum control and grip while still maintaining optimal efficiency, generating less friction and more speed. As the skiers raced down the course on the screen, so did Jørgen’s brain as he sat in front of the TV, molding deeply abstract physical concepts into something that could work in the real world, when suddenly…

The flash of clarity hit him like a ton of bricks and Jørgen shot up straight in his chair. All the thoughts swirling in his mind suddenly coalesced into a clear vision, the rush of lucidity literally taking his breath away, his mouth turning up into a small smile as he recognized the significance of the moment.

It was jarring in its simplicity, really. By gradually raising the edges off the snow from totally perpendicular at the end of the binding to three or four degrees of bevel towards the tip and making the entire ski torsionally softer, turns would be easier to initiate and smoother once the entire edge engaged with the snow as the skier leaned into it. Combining this singular insight with the budding parabolic sidecut technology and a traditional cambered profile meant Jørgen’s design concept would be capable of providing performance results that would revolutionize the world of ski geometry and construction. Or so he thought…

Jørgen immediately set to work on refining his idea whilst simultaneously running the family business. He wasn’t much of a skier but he was good enough to iron out most of the kinks on his prototype skis while he shopped the concept around to all the big companies: Atomic, Völkl, K2, Rossignol. In fact, it was a fellow Scandi who worked at Rossignol who told him to be wary of sending his unpatented ideas to every brand in the industry, as they would gleefully steal his intellectual property. Jørgen also heard back from a biodynamics expert who did some consultancy work for K2’s ski and snowboard development programs, and the resounding message he got from everyone he spoke to was that this idea could not work.

While it was nice to get feedback from such esteemed folks, ultimately Jørgen’s concept was already viable and every single ski company he approached had scrapped the exact idea that now makes Bataleon snowboards work better than any other snowboard in the world. Although disappointed, he knew that revolutionary ideas are hard sells for established companies so he kept plugging away, despite still having every door he knocked on slammed in his face. The struggle continued for a few years with the ski industry, with Jørgen getting a lot of pushback on his 3D shaping concept, despite brands having eventually adopted sidecut and torsionally softer skis.

Meanwhile, snowboarding was picking up a lot of momentum and increasingly becoming a part of the zeitgeist, its growth rate more akin to a cultural phenomenon than a just another winter sport. Jørgen’s daughters were hip to sliding sideways and it wasn’t long before he decided to test his concept on a snowboard. Although he didn’t know it at the time, the moment he strapped into his first Triple Base board was history in the making.

It only took a few turns for Jørgen to realize that his concept’s advantage gains were much, much bigger on a snowboard, since it was so much easier to catch an edge on a snowboard due to its shorter, more aggressive turn radius. For comparison, even slalom skis have a 12-meter turn radius, so snowboards —whose sidecuts range from 6 to 10 meters— have a more dynamic sidecut than any ski out there. This means snowboards need all the help they can get to avoid catching an edge, especially when tracking straight.

Riding that first snowboard was a true revelation and the more Jørgen worked on his prototypes, the better his idea worked. The snowboard industry was young and thriving, being more open to new ideas and tech, so in 1998 he filed a patent for Triple Base Technology* and never looked back, never working with skis again.

*Make sure you check out the 3BT Tech section to get the full skinny on how Triple Base actually works.

HIGH-TECH TURNS

Jørgen knew he had solved the conundrum of the ideal shape, but now he had to convince the rest of the snowboarding world that Triple Base Technology worked. Despite snowboarding’s openness to new ideas, getting a new brand off the ground was definitely no walk in the park and there were more than a fair share of haters who wrote off Triple Base as nothing more than a gimmick.

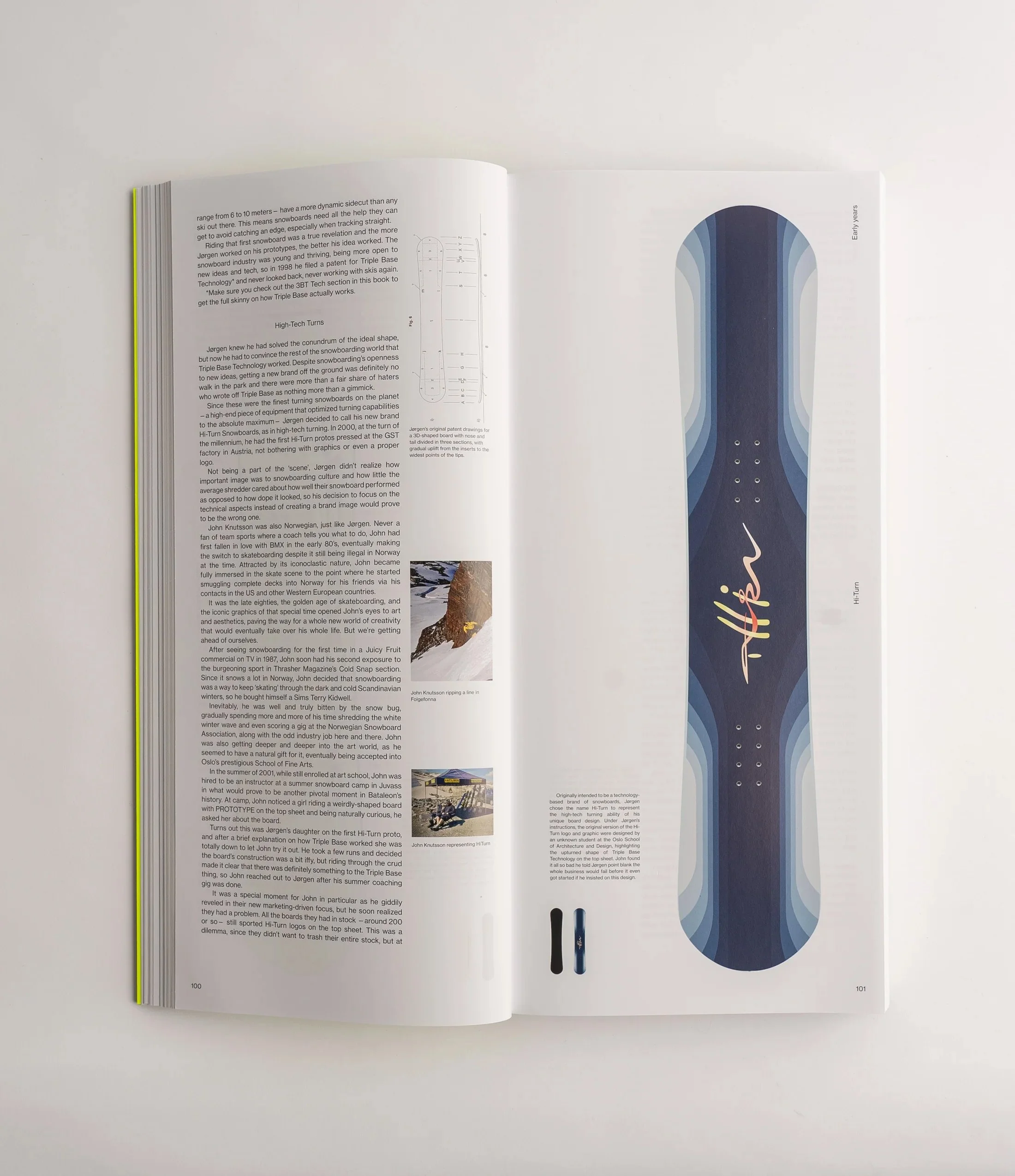

Since these were the finest turning snowboards on the planet —a high-end piece of equipment that optimized turning capabilities to the absolute maximum— Jørgen decided to call his new brand Hi-Turn Snowboards, as in high-tech turning. In 2000, at the turn of the millennium, he had the first Hi-Turn protos pressed at the GST factory in Austria, not bothering with graphics or even a proper logo.

Not being a part of the ‘scene’, Jørgen didn’t realize how important image was to snowboarding culture and how little the average shredder cared about how well their snowboard performed as opposed to how dope it looked, so his decision to focus on the technical aspects instead of creating a brand image would prove to be the wrong one.

John Harald Knutsson was also Norwegian, just like Jørgen. Never a fan of team sports where a coach tells you what to do, John had first fallen in love with BMX in the early 80’s, eventually making the switch to skateboarding despite it still being illegal in Norway at the time. Attracted by its iconoclastic nature, John became immersed in the skate scene and was one of many Norwegian skate kids who smuggled skateboards into Norway while on trips abroad.

It was the late eighties, the golden age of skateboarding, and the iconic graphics of that special time opened John’s eyes to art and aesthetics, paving the way for a whole new world of creativity that would eventually take over his whole life. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

After seeing snowboarding for the first time in a Juicy Fruit commercial on TV in 1987, John soon had his second exposure to the burgeoning sport in Thrasher Magazine’s Cold Snap section. Since it snows a lot in Norway, John decided that snowboarding was a way to keep ‘skating’ through the dark and cold Scandinavian winters, so he bought himself a Sims Terry Kidwell.

Inevitably, he was well and truly bitten by the snow bug, gradually spending more and more of his time shredding the white winter wave and even scoring a gig at the Norwegian Snowboard Association, along with the odd industry job here and there. John was also getting deeper and deeper into the art world, as he seemed to have a natural gift for it, eventually being accepted into Oslo’s prestigious School of Fine Arts.

In the summer of 2001, while still enrolled at art school, John was hired to be an instructor at a summer snowboard camp in Juvass in what would prove to be another pivotal moment in Bataleon’s history. At camp, John noticed a girl riding a weirdly-shaped board with PROTOTYPE on the top sheet and being naturally curious, he asked her about the board.

Turns out this was Jørgen’s daughter on the first Hi-Turn proto, and after a brief explanation on how Triple Base worked she was totally down to let John try it out. He took a few runs and decided the board’s construction was a bit iffy, but riding through the crud made it clear that there was definitely something to the Triple Base thing, so John reached out to Jørgen after his summer coaching gig was done.

The two got along pretty well and John eventually felt comfortable enough to make some pointed comments about the direction of Hi-Turn as a brand, despite his being on board with Triple Base Technology as a whole. John felt there was far too much emphasis on the technical aspects of the boards and not enough on the brand, but Jørgen felt the technology would sell itself and marketing it was a waste of time and energy.

By 2002, Jørgen had reluctantly designed a gradient top sheet graphic with an unknown student from Oslo’s school of architecture that highlighted the Triple Base concept, along with a highly stylized Hi-Turn logo. Once he got his hands on one of the new boards, John —being conversant in the things that made snowboarders happy— realized this graphic would doom Hi-Turn as a brand if it was ever released into the wild. John wasted no time in telling Jørgen that this graphic was unacceptable.

Around this time, OG Norwegian shred legend Ståle Lien also got involved with the company. Possessing god-level shred skills, Ståle had a keen eye for tech stuff as well and he quickly realized the game-changing potential of 3BT. He also happened to agree with John about the gradient graphic and the Hi-Turn logo.

A deeply rational man, Jørgen realized he was barking up the wrong tree, John and Ståle were right about the importance of the brand’s image and the gradient graphic boards were pulled before being shipped to stores. But he was adamant about keeping the name, so John quickly drummed up a stop-gap solution, designing a simple yet bold Hi-Turn logo which he paired on the top sheet with crisp, narrow lines that showcased the board’s Triple Base Technology. He still didn’t like the name, but at least he could live with the new graphics.

Hi-Turn’s sales weren’t exactly brisk once winter 2002/2003 rolled around, but they weren’t a complete disaster, either. John and Ståle also made sure they hooked up the right people in the Norwegian snowboard scene with a board so they could see for themselves that Triple Base was going to thoroughly revolutionize snowboarding. Most were skeptical at first, but they all realized 3BT worked as soon as they laid into a carve.

BATALEON, BABY!

On the day John graduated from art school in spring 2003, Jørgen immediately hired him as brand manager, a role John had never really played before. This meant a lot of improvisation and flying by the seat of their pants, but everyone was determined to make it work. Bringing 3BT to the world was a more than worthy cause in their minds.

After constantly hounding him about how Hi-Turn would never work as a brand if they continued to focus exclusively on the performance of the boards, Ståle and John had finally worn Jørgen down and he capitulated. Henceforth, they would be focusing on the most important aspect of any snowboard company: creating and marketing an image. But for that, they were going to need a fresh start.

In their eagerness for feedback on Triple Base Technology and the rush to establish Hi-Turn as a brand, they had made the mistake of hooking up way too many people with a free deck, diluting the brand’s value and creating a sort of backlash against them in the Norwegian scene. This meant a complete rebranding was called for if they wanted to survive.

When the time came to pick a new name, John brainstormed with Ståle and Jørgen for hours, spitballing and throwing ideas around till they narrowed it down to a couple they really liked. John had come up with ‘Bataleon’ because it was catchy and stood out, the name wasn’t deliberately inspired by anything military but they certainly wanted to arm a cadre of shred ninjas with a revolutionary mountain assault weapon, if you will. Meanwhile, Ståle’s suggestion was ‘Undisputed’, which John actually preferred to his idea. But both Ståle and Jørgen liked Bataleon better, so that’s what they went with.

The quirky spelling was simply because John wanted to register a domain that didn’t require the word ‘snowboard’ after the brand name, which he thought looked tacky. If they stuck with Battalion, they would be forced to use battalionsnowboards.com so they settled on John’s funky version instead, registering bataleon.com as their url. It never occurred to the three men at the time that their little brainstorming session would lead to twenty years of unmitigated chaos, beauty and, above all, fun.

Thus was born Bataleon.

It was a special moment for John in particular as he giddily reveled in their new marketing-driven focus, but he soon realized they had a problem. All the boards they had in stock —around 200 or so— still sported Hi-Turn logos on the top sheet. This was a dilemma, since they didn’t want to trash their entire stock, but at the same time they couldn’t sell them with the old Hi-Turn logo still on there.

So John came up with a guerrilla solution, printing out large stickers with the brand-new Bataleon logo he had just designed and plastering them atop the Hi-Turn logo on every single one of those old decks. It wasn’t ideal but it took care of the leftover boards, tiding them over for another winter while they focused on creating new 3D shapes, designing new graphics, and finally putting together a team. Rumor has it some of those stickered boards are still out there, in the hands of older shreds and collectors.

For the rest of 2003, John, Ståle, and Jørgen worked extensively on rebranding and getting the new boards pressed, hiring Frode Lunde, another Norwegian with experience in the snowboard industry, as the Sales Manager. They were still dealing with the fallout from the Hi-Turn debacle of over-saturating the Norwegian market with freebies in their haste to prove that 3BT worked, but Bataleon was slowly picking up steam as people across the rest Europe and increasingly in North America showed interest in ‘those crazy Scandis’ and their even crazier Triple Base Technology.

2004/2005

Produced at: GST

Creative Director: John Harald Knutsson

Contributing artists: Morten Slettemeås

Shapes by: Jørgen Karlsen

Team riders: Julian Karlsen, Christian Halland, Brett Butcher, Andreas Gidlund

The winter of 2004/2005 marked the debut Bataleon’s inaugural collection, which included three models: Goliath, The Hero and The Enemy. Designed and shaped by Jørgen, all three shapes were built on the same first-generation Triple Base template, with a 1/3 - 1/3 - 1/3 breakdown for the center base and two side bases. The flex pattern was also the same for all three boards and could be described with one word (and an expletive for good measure): fucking stiff.

Sales were nothing to write home about, which was to be expected for a brand fresh out of the gate, but John and team manager Ståle Lien made sure the right people were sent Triple Base Technology-built boards in order to build some rapport in the industry. They also hit every major event on the calendar, including the European Open in Livigno and the Arctic Challenge in Tromsö, just to get the word out that the Triple Base revolution was here. Along with enormously talented team riders like Julian Karlsen (no relation to Jørgen) and Tore Holvik, they cruised the shredosphere far and wide, stickering everything in sight, raising hell and having fun. John, Ståle and the riders weren’t trying to act ‘cool’, they were just being real, real enough that the industry took note.

This winter also marked their first-ever trip to the most important European snowboard industry gathering of the year, the ISPO trade show in Munich, Germany. After contacting ISPO, they were given a space in the ‘free booth’ section, which ISPO has used to help promote many a fledgling brand over the years. They set up their tiny stand —if you could call it that— with a curtain backdrop, a poster board sign with the Bataleon logo and a few boards scattered about. Interestingly, future part-owner and CEO Dennis Dusseldorp was also in attendance at ISPO that year working as a sales rep for Nitro, when a buddy of his who lived in Norway bought one of the stickered-over Bataleon samples for very cheap at the end of the trade show. A few weeks later Dennis visited his friend and rode his very first Triple Base snowboard on the hills around Oslo, still unaware of what the future held in store for him and Bataleon.

Since every ‘proper’ snowboard brand needed a catalog, John decided to put together their very first printed catalog together with designer Sverre Skjold. The previous winter (2003/2004), Ståle Lien and Espen Amundgard had become the first and only snowboarders to successfully huck backside spins over the Arlberg road gap and ride away clean, both dudes accomplishing the mighty feat on Bataleon Triple Base snowboards. So John used the still photos and sequences of them clearing the face-meltingly massive gap in the 04/05 catalog, with Espen scoring the cover.

Bataleon’s journey had begun with a small, but bold, step, firmly announcing to the snowboard world that they were here to stay.

2005/2006

Produced at: GST

Art Director: John Harald Knutsson

Contributing artists: Brian Højmark Larsen, Roger E.P. Egseth, Morten Slettemeås, Alexander Muskaug

Shapes by: Jørgen Karlsen (Ståle Lien, John Harald Knutsson)

Team riders: Julian Karlsen, Christian Halland, Brett Butcher, Andreas Gidlund, Nick Visconti, Gulli Gudmundson, Tyler Chorlton

By their second season as Bataleon, Jørgen, John, Ståle, and Frode had realized there was enough interest in Triple Base Technology for them to expand their line and create more specialized models, including their first-ever women’s specific board, the Violenza. This model featured a much softer flex, both longitudinally and torsionally, to accommodate for women’s smaller frames but it turned out lots of smaller dudes also preferred the softer flex of the Violenza.

With the majority of snowboarders —and pretty much 100% of the industry— at the time focused on park and freestyle, it was clear they needed a true twin design in the collection. Since twins need to work well when landing jumps and sliding rails, Jørgen made a new flavor of Triple Base with a wider center base that sacrificed a bit of float for increased stability, in the process creating one of the most legendary boards in the history of snowboarding: the Evil Twin. Still in the line today, it is by far Bataleon’s top-selling board of all time.

The third new board in the line was the Undisputed, the same name that Ståle had suggested for the brand during that legendary brainstorming session. This was a freeride-specific, fully directional shape that led to the creation of yet another flavor of Triple Base shaping, this time with a narrower center base for increased float in powder.

The fourth new design was called Project X, a super stiff, ultra-responsive rocket built to dominate boardercross. Team rider Oeystein Wallin would go on to take first in the snowboard cross event at the World Junior Snowboard Championships that season, proving that Triple Base Technology worked in the most demanding environments. After all, 3BT had been originally created for faster, more efficient turns, so it made sense that it was a monster on the boardercross circuit. But John and Ståle decided this wasn’t the direction they wanted the brand to go, and the Project X was Bataleon’s first and last foray into boardercross.

For their second visit to ISPO, once again the organizers hooked them up with a free booth in the ‘Brand New Village’ section for start-up brands. Since it was a much larger space than the year before, they needed to have an actual booth so John bought a shitty old camper trailer, filled it to the rafters with boards, stickers, posters, and other promotional material and drove the 1,600km from Oslo to Munich. Once there, he simply drove the caravan into the hall and parked it. This would prove to be a pivotal moment in Bataleon’s history, as across the hall from their booth was the Groovstar stand, manned by two young Dutchmen.

Dennis Dusseldorp was a young skater and windsurfer from The Hague who had studied sports education. During his studies, Dennis went on a field trip to the Alps and finally had a chance to strap into a snowboard. By the end of his first week on the hill, he had been bitten hard by the snow bug, signing up the day he was done with school to be a snowboard instructor for a Dutch travel agency, which was pretty rich considering he didn’t really know how to snowboard properly yet. But he looked and sounded like a snowboarder, so the travel agency was sufficiently impressed to give him the job.

When he arrived in Serre Chevalier in 1995 to teach neophyte Dutchies in the fine art of sliding sideways, Dennis could barely snowboard but he made do as best he could. It was still his first week there when he ran across a Kiwi snowboarder called Cleay Perham, who was also living the ‘seasonnaire’ dream. The two hit it off immediately, becoming instant best buddies and snowboarding literally every day. They quickly progressed and their bond grew even stronger, Cleay eventually going on to play a key role in the future of the company, as we shall soon see.

After following Cleay around Serre Chevalier, Dennis got good enough to be put on the Nitro Benelux team. The two friends would continue doing seasons together, first in Risoul and then La Plagne, Dennis managing to win the Benelux boardercross championships in 1997. Cleay would eventually make his way to the States, spending several seasons in Colorado then head straight back home to New Zealand to catch the winter there. All in all, he did 16 back-to-back seasons and it would be 8 long years until Cleay saw another summer.

With a few seasons in the French Alps under his belt and hustling to get by as the Benelux sales rep for Nitro Snowboards, Dennis had been convinced by his-then girlfriend —a TV producer— to audition for a part on a promising new show. Dennis got the part, despite his lack of experience as an actor, and in the summer of 2000 his face was being beamed into the TVs of literally millions of Dutch homes. He would continue to play the role until 2002 because the money was good, but becoming an overnight celebrity in the Netherlands had messed with his head and Dennis decided he’d had enough. So he hit up Cleay, who was back in New Zealand, doing design work for a local outerwear brand called Groovstar. Cleay invited Dennis to come down so he did, moving full-time to NZ and completely bailing on the TV show, ditching a potential life of fame to go shred and hang with his old buddy. It didn’t hurt that they lived right across the street from one of New Zealand’s finest lefthand point breaks, either.

Once there, he started working as Sales Manager for Groovstar, while Cleay did the website and designed the gear. Things were picking up for Groovstar, as Dennis worked his international contacts, and Cleay soon needed an extra hand with the design work, so they hit up another old friend of theirs, an all-around ripper and creative wunderkind named Danny Kiebert.

Danny and his younger brother Ruben —aka Rubby— had grown up in a small village not far from Schiphol airport. They were the only skaters in their village, except for two other kids. Some summer vacations were spent in Israel visiting their relatives from their mother’s side. Israel was much closer culturally to the US than the Netherlands, Tel Aviv actually had skate shops and a skatepark!

It was on one of those summer trips that the two brothers discovered surfing in 1982. Back home, Danny fell in love with the speed and technical difficulty of windsurfing, spending all his days on the lake next to their village. The first time Danny connected with snowboarding was on a birthday party from one of his windsurfing buddies. An hour of sliding on an artificial slope made out of nylon brushes was all it took to start a lifelong passion. Rubby would soon join in weekly missions by bus to the plastic mountain in Hoofdorp. After convincing their parents to go on the family’s first-ever winter holiday to Mayrhofen, Austria, it was on! Rubby dropped out of school as soon as he could to head for the mountains, doing multiple seasons in a caravan in Zillertal and after that seasons in the European capital of freeriding: Chamonix. Later he would spend time with Dennis and Cleay in the French Alps in the mid- to late-90s.

Meanwhile, Danny went to live in Rotterdam, where he studied Design & Communications while going on back-to-back snowboard missions. Enamored of urban culture, Danny was skateboarding, exploring new digital art forms and musical genres, working with the internet that was just starting to become a thing next to publishing his own magazines. They actually started as fanzines, of course, but Danny had quickly become adept at graphic design and words came naturally to him, the quality of his content affording him a significant audience of culturally-savvy and worldly young adults. He would soon be appointed chief editor of Air22, one of the leading snowboard magazines in Holland during the mid-90s. (Random fact: Air22 did a ‘young blood’ checkout on Dennis before Danny and Dennis officially met!) By the late 90s, both Kiebert brothers were well-established names in the Dutch snowboard scene, having ridden for string of brands through local distribution. Danny went from Sims to Black Flys, then Atlantis, then Donuts, and finally Burton, for whom he would also organize the Dutch stop of their movie tour to sold out cinemas. Meanwhile, Rubby went from Shorty’s to Nidecker.

Somewhere around this time, Danny and Rubby connected with their friend Dennis, who Rubby had first met during one of his La Plagne visits and who Danny eventually met when he went there to spend a few weeks shredding with his little brother. Later Rubby would also team up with Dennis, running surf camps in the south of France and finding all kinds of creative ways to part the buses of tourists who came to the camps from their money.

For the following year and a half, Dennis was living full-time in New Zealand working for Groovstar and Nitro, while Danny continued to focus on his multi-pronged creative endeavors in the Netherlands, making mags, websites, music, and so much more, including design and marketing work for Groovstar. Which finally brings us back around to the Groovstar booth at ISPO 2005, located directly across the hall from Bataleon’s crappy caravan.

When Dennis found out that ISPO had given Groovstar a free space in the Brand New Village that February, he hit up Danny and asked him if he’d come out to Munich to help him man the booth for the duration of the show. Always down for an adventure, Danny immediately said yes. It’s true that fortune favors the brave, because Danny’s decision to join Dennis would prove to be a fateful turning point in both their lives.

Once the show got started on Sunday, they immediately took notice of Bataleon and all the hype they were generating. There was a definite buzz around the camper van/booth and, being amenable to fun, it was inevitable that Dennis and Danny would eventually cross paths with the hard-charging Norwegian crew. They all took an immediate liking to each other and after seeing Dennis and Danny’s interest in Triple Base, John quickly introduced them to Jørgen, who dazzled them with his blisteringly sharp intellect and full dominion of the then-completely novel technical aspects of 3D shaping. Jørgen picked Dennis’ brains about all sorts of things, but in particular international sales. He seemed eager to get Dennis onboard, but had clearly bet on Frode Lunde to do the sales job, so no real offer came… yet.

Back at ISPO, it was the last day of the show and John and Frode were packing the camper trailer for the long drive back to Oslo, while Dennis and Danny broke down the Groovstar booth. Frode, almost jokingly, asked Danny what he thought about hopping in the car and driving with him all the way back to Oslo for a photoshoot with a few of the Bataleon team riders. Never having attended such a thing, nor even having witnessed a pro snowboarder do their thing live and in person, Danny immediately accepted the offer and told Dennis he was gonna head out with Frode. It turned out to be another fork in the road of the brand’s story.

It was a long ass drive but once in Norway, Danny was blown away by it all, the professionalism and mind-blowing skill of the riders, the focus of the media crew —photogs and filmers alike—, the hype and excitement around Bataleon, even the way they seemed to have bottomless funds. Which of course, wasn’t the case, as Jørgen was footing the bill entirely, but Danny had no way of knowing that then.

So after a couple of days, he reached out to Dennis and told him to come up to join them at the shoot, cuz shit was going off. So Dennis comes up and everyone was partying like their life depended on it, in particular Sales Manager Frode Lunde. A few days later, the shoot finally wrapped and everyone headed back to their respective homes.

In the spring of 2005, a couple of months after the shoot, Dennis received a phone call from Jørgen, offering him a full-time job as Bataleon’s Sales Manager. Turned out that Frode was worried that the snowboarding party lifestyle was going to be the death of him, literally. Dude was drinking himself to death and was afraid he would lose control so he just straight up quit, hanging Bataleon out to dry. So Dennis made Jørgen a counterproposal, telling him that he was quite happy doing Groovstar and Nitro, not to mention living part-time in NZ, ‘what can you offer me to sweeten the deal enough for me to quit and join Bataleon’? So after a few rounds of negotiation, Dennis took the International Sales Manager job in return for a small bit of equity in the company, because at that point of his life he just really wanted to own something himself.

With John and Ståle heavily focused on making an impact in the US market, they had convinced Jørgen to open a North American subsidiary, which they tasked Dennis with as his first major assignment for Bataleon. So Dennis flew out to the States and headed straight to Oregon, figuring Welches —a tiny town at the base of Mt. Hood and its world-renowned glacier— would be the epicenter of everything that was rad in snowboarding. Dennis would end up spending the majority of his first year as Sales Manager in the US, living and working in an AirBNB in boring and rainy Welches for two straight winters with Tine and their two girls, while both Danny and John would come out to spend several months shredding and working on growing the brand’s reach. The first batch of boards for the US market were actually kept in the spare bedroom and they would ship them out themselves.

The final piece of the puzzle of that hugely significant year for Bataleon was the contract that Jørgen signed with Fred van Haren and Benoit Gavage, co-owners of Atila Network, one of the largest distributors of skate/snow brands in Belgium and France. Their contacts and expertise would add greatly to sales efforts, was the rationale behind the deal. Things were moving steadily forward, even if sales had yet to reflect the overwhelmingly positive feedback from the industry on Triple Base Technology.

2006/2007

Produced at: GST

Art Director: John Harald Knutsson

Contributing artists: Roger E.P. Egseth, Danny Kiebert

Shapes by: Jørgen Karlsen (Ståle Lien, John Harald Knutsson)

Team riders: Julian Karlsen, Christian Halland, Andreas Gidlund, Kalle Ohlson, Brett Butcher, Nick Visconti, Gulli Gudmundson, Mitch Brown, Vicki Miller, Tyler Chorlton

In 2006/2007 things were looking pretty sweet. Dennis was still posted up in Welches with his wife Tine and their kids, focused on developing as many sales channels in as many markets across the world as possible and also working hard at being the best dad he could be, while John and Danny made extended visits to Oregon during that winter and spring. Ståle preferred to spend most of his time traveling with the team riders within Europe, while Jørgen tended to his tulip business for the time being, as no new boards were introduced that season, requiring no 3D shaping from him.

They did, however, introduce Bataleon bindings, which were actually more of a collaboration with SP, an established binding brand from Austria with a bomb-proof baseplate and a highly responsive metal heelcup, They chose an odd name —The Allies— but the hibacks were solid and the straps as comfortably lush as anything else available at the time, making these stripy binders a fine addition to the line, even if Bataleon still didn’t own or fully understand the technology used in creating them.

John’s role as Creative Director meant he was responsible for designing graphics for the entire line, along with marketing, dealing with all the media and ad buys, testing and fine-tuning boards and traveling with Ståle to demos and events with the team. Meanwhile, Danny had finally realized a lifelong dream of having his work used as a graphic on a snowboard (although he would have been equally as stoked if it had been a skateboard) when Bataleon chose his original five-fingered hand logo for the new iteration of the very popular Evil Twin. The hand was included in a batch of graphics that Danny had submitted to John and Jørgen, and would prove to be first of very, very many he would design over the course of the next 20 years.

In the meantime, they all continued promoting Bataleon by showing up at all the biggest contests, events and trade shows in the snowboarding world, including SIA —the US snowboard industry’s most important gathering of the year— for the first time. It was January, 2006 when Danny and John made the long drive down from Welches to Las Vegas. Yes, for over a decade the biggest and baddest event in all of snowboarding was held in Sin City, can you imagine the levels of debauchery and debasement? Anyhow, Danny and John built the Bataleon booth at SIA, giving lots of people in the States their first chance to stop perving out at catalog photos and finally fondle a real life Triple Base board, then hopped on a plane and flew directly to Munich for ISPO, where Fred and Ben from Atila had already built the stand, and did it all over again. Dennis and Danny actually saw Jørgen talking to Lib Tech’s legendary founder Mike Olson at the show in Munich, where he picked Jørgen’s brain for almost two hours. When Dennis and Danny asked Jørgen if he knew who he was talking to, the blank look on Jørgen’s face said it all. The following season Lib Tech would introduce the Skate Banana as Mike found his own way to bend boards to avoid catching an edge. But we are getting way ahead of ourselves here.

Snowboarders claim to be open-minded, but the industry has always been just as cliquey and guilty of gatekeeping as any other business. Back then snowboarding was more about how hard you could party and still land your tricks the next day, and although Danny has literally never touched a drop of booze, cigarettes, drugs, or caffeine in his life, the rest of the crew more than made up for the slack, which gave Bataleon a rep for keeping it real and doing it for all the ‘right’ reasons. There was a lot of partying but there was a lot of working, too. It was actually all the same thing, which makes total sense if you were involved in the industry back then, and possibly not if you weren’t.

In early April, 2006, John rounded up a gaggle of Bataleon riders for the Transworld Team Challenge at Aspen Buttermilk, a light-hearted event where brands competed for a number of different awards, including best costumes. So John found matching orange fisherman outfits for the whole crew and a rambunctious time was had by all, further cementing Bataleon’s status as a legit brand in the eyes of the US media’s most influential mags like TWS and Snowboarder Magazine. Of course, anything that was cool in the US was automatically considered legit in Europe, with Onboard and Method Mag also showcasing a ton of Bataleon riders and products in their pages, the brand even getting some love from super core Japanese publications like Snowstyle. John’s media savvy and strategically placed ad buy-outs were paying off in spades.

So it was no surprise that sales were picking up a head of steam, despite the inevitable blips on the radar. Dennis had gone through a bad experience with a person he had hired to handle the North American accounts, and was still looking for someone with a solid industry background to help him with the ever-increasing workload. He had finally given up on soggy Welches, moving his entire life (including Tine and the kids) to a new spot in Tacoma, WA in mid-2007. Dennis had chosen Tacoma due to its proximity to Seattle and also because he had met other enterprising dudes who were starting up a wakeboard brand called Imperial Motion. IM’s brand ethos shared a lot of the same iconoclastic tendencies as Bataleon, so it was a good fit as the two companies could share office and warehouse spaces. There was even a full-blown screen printing operation set up in the back of the warehouse, so it was the ideal set-up and mutually beneficial at the time.

John was growing increasingly frustrated that he couldn’t dedicate more of his time to making the best graphics possible, as he was just getting pulled in too many directions by the different responsibilities of his job. By the end of 2007, after some back and forth with Jørgen and Dennis, they all agreed to invite Danny to take on a more prominent role in the company, focusing mainly on designing board graphics and giving John some breathing room for his other roles. Danny was highly skilled at using the computer and graphic design software, which allowed him to very quickly flesh out and develop John’s concepts into solutions that were more commercially viable and making everyone’s life a bit easier.

Danny had since left Rotterdam and moved to Amsterdam full time, renting a small studio space to work in. That summer of 2007 John flew down to Amsterdam from Oslo to work on board graphics and marketing materials with Danny in his little loft, as they worked on another significant expansion to the line in the following year.

2007/2008

Produced at: GST

Art Director: John Harald Knutsson / Danny Kiebert

Contributing artists:

Shapes by: Jørgen Karlsen (Ståle Lien, John Harald Knutsson)

Team riders: Andreas Gidlund, Kalle Ohlson, Brett Butcher, Nick Visconti, Gulli Gudmundson, Julian ‘L’arrogs’ Haricot, Mitch Brown, Ben Rice, Vicki Miller, David Bertschinger Karg, Tyler Chorlton

This season saw the advent of a number of new models in the collection, including the Distortia, Bataleon’s first-ever women’s twin. After the immediate success of the Evil Twin, the design crew felt there was room in the market for a serious park board for women.

Speaking of the Evil Twin, the decision was made to keep it more affordable, so a new model was called for in order to fill the niche for a stiffer, specced-up true twin for everyone that wanted to go the biggest in the park. We called this new high-end twin the Riot.

Next up was the Fun.Kink, an all-terrain directional twin that was perfect for all sorts of riding, nothing too serious, just something fun that everyone and anyone could jump on. It was also a dig at Burton, since this was the height of the Un..Inc days, their attempt at pushing an anti-corporate agenda while being the most corporate company anyone could think of, so John and company wanted to call out how ridiculous they thought the whole thing was.

The Jam was essentially a rebrand of The Hero, as it was decided that the name sounded a bit too cheesy for a board that was meant for more serious riding than the Goliath. In hindsight, it’s not entirely clear if Jam was that much better as a name, but at least it was something different.

Since Bataleon now had at least two flex variations in each category, they also wanted to offer something with a softer flex in the freeride category, to counterpoint the stiffer Undisputed model. Enter the Locust. However, freeride remained a tough category for them to build out, probably due to the fact that the team leaned heavily towards park and street, so the Locust was only kept in the lineup for this one season, while the 2007/2008 Evil Twin Ltd was Bataleon’s first-ever limited edition board, the magenta and neon green graphic still regarded as one of the ET’s most iconic of all time.

Two more bindings were introduced to the line: a women’s version of The Allies and the Thunder for the men, a moniker we will see return again 13 years later on a snowboard. These were again produced in collaboration with SP, taking full advantage of their badass binding design. Another hallmark of that year was the adoption of the “Yeah For It!” tagline. The sentence, which wasn’t even proper English, was basically invented by then-team rider (and later team manager) Julien ‘L’Arrogs’ Haricot. In his characteristic drawling Frenglish, L’Arrogs would shout “Yeah For It!” all the time to express his enthusiasm, regardless of the situation. It was a combo between ‘yeah!’ and ‘go for it!’, which didn’t make sense whatsoever but everyone loved it and thought it suited Bataleon perfectly.

Around early 2007, Tyler Ketz —currently Managing Director for North America for Bataleon and all other associated Low Pressure Studio brands— first met Dennis in Tacoma. Tyler was originally a baseball player who fell in love with board sports and the culture when he visited the San Diego area for a baseball tournament. He started snowboarding fairly late, already a college student when he first strapped in, but that didn’t stop Tyler from chasing his dream of scoring an industry job. So he applied for a job as an intern at Transworld Business magazine, and literally went from living at home in Washington State to living in Oceanside, California with nothing to his name and no place to live seemingly overnight.

Tyler eventually found his way and spent a year learning the ropes from industry vets, something that is part and parcel of the amazing opportunity of interning at TWBiz. As his year in Oceanside was coming to an end, Tyler pitched a story to his editor Leah Crane about a group of friends who had launched a wakeboard brand in Tacoma called Imperial Motion, which was the brand that was sharing office and warehouse space with Dennis and Bataleon’s US operation. Leah approved the story, so Tyler boned up on his wakeboard industry lingo and serendipitously headed out to do the piece.

Arriving at the shared facility, Tyler was rocking a Burton hat and t-shirt when he was introduced to Dennis, who after mere minutes of small talk said to him, “you know, there’s two things I hate in this room, one is your hat and the other is your t-shirt”. Dennis followed that statement up by offering to trade Tyler’s Burton tee for a Yeah For It! shirt, which Tyler promptly agreed to, getting his first taste of Bataleon world and what he likes to call ‘Dutch direct’. They continued to chat and Dennis explained how he was looking for someone to assist him in helming the ship in North America. This definitely piqued Tyler’s interest, as it seemed like the ideal position for him, but he drove back home empty-handed, for the time being, at least. Dennis needed a sales manager with experience and despite Tyler being a great guy, honest, and trustworthy, he was not the sales guy Dennis was looking for just yet.

So Tyler lined up a gig at Safeco Field —the Seattle Mariners baseball team home stadium— but his heart wasn’t in it, leaving after just a few months for a job managing corporate lift pass sales at Stevens Pass ski resort, which gave him the opportunity to shred as much as possible every single day. Tyler knew he needed to pay his dues if he was going to get a legit job in the snowboard industry, so he found a place to live across the street from the resort and made the most of every day. The fact that it was an insane winter at Stevens that year with epic conditions just made it all that much sweeter. Tyler learned to shred pow and hit jumps, he reveled in the weekly line-up of events and kept in touch with Dennis that whole winter.

This part of Bataleon’s history would not be complete if we didn’t mention Tim Bean, who was doing an amazing job representing the brand and establishing the initial groundwork in the US market at the time. Tim, who is Michigan-based, had come onboard right at the very start in 2004, when the Bataleon ‘office’ was still in Welches. Tim had already established some solid lines of retail across the country by this season, and after leaving Bataleon would go on to start his own marketing and management agency called Driven. Today, Tim works as an executive in the defense industry.

Then, in January 2008, one of the most pivotal moments in Bataleon’s history —informally known as the ‘Great Canadian Border Incident’— would go down, tearing a hole in the space-time continuum and sending the company hurtling towards a new reality that no one was really prepared for. Basically, Dennis and Danny had driven up to Vancouver from Tacoma to pay a visit to their Canadian distributor and visit some shops, thinking nothing of crossing the border as they believed their visas were in order. Which they were, but that didn’t stop a US Customs and Border Patrol agent from denying Dennis reentry into the States after inspecting his passport. Danny was allowed through but, despite all his cajoling and the fact that his visa was actually valid and in order, Dennis was not permitted to enter the country. Having no wish to escalate the situation and unwilling to let it bum him out, Dennis drove back to Vancouver certain everything would be resolved within 48 hours, while Danny headed back to Seattle to reunite with Dennis’ wife Tine, and their two young daughters.

But after calling the US embassy in Vancouver and being told that the next available appointment was at least 5 weeks away, possibly even longer, Dennis began to lose hope, realizing this wasn’t going to go away quickly or easily. So right then and there he made an executive decision to call it quits on North America and return to the Netherlands full-time. That meant he needed someone to help Tine close up the apartment, gather the family’s belongings and get everyone on a plane back to Holland. Luckily Danny was still in Tacoma and could help sort everything out.

But it also meant Dennis needed to find someone to run the Bataleon operation in the US in his absence, so he reached out to Tyler, easily their best option on such short notice. After debating with Jørgen if it was worth hiring someone who had recently graduated from college for such a vital position in the company, they decided they would go with their gut and give Tyler a shot. After all, he was obviously sharp as a tack and had a natural gift for finance, operations and logistics, only lacking experience with sales and marketing to be the perfect candidate. So Jørgen and Dennis had an idea: they would hire someone with plenty of sales chops to help complement Tyler operational skills, that way they could cover all their bases.

An interview was scheduled in Vancouver late spring 2008 with both Tyler and another US-based sales rep named Joey Bruey who was already working with Bataleon and Celsius and had plenty of experience selling snowboards. The interview was basically a formality, and both Tyler and Joey started their new roles just a couple of weeks after their meeting with Dennis and Jørgen in a random hotel just over the border. Bataleon’s arc had taken a radical turn, all because of some dumb Border Patrol asshole who decided he didn’t like the look of Dennis’ face, and now all his focus was on setting up a proper office in Amsterdam so they could continue to grow the brand even more globally, as they now had distributors in place from the United States to Japan and across Europe.

However, the approach favored by Dennis, Danny and John was anathema to team manager Ståle Lien, who believed they had outgrown their britches and should reel the business back in to a more manageable state, making sure their OG riders and employees —the people who had first put Bataleon on the map— were taken care of before they spent any more money on expanding their sales globally. Ståle felt he and the other original riders were being snubbed, gradually nudged out of what was rightfully theirs in favor of new global recruits. This inevitably led to increasing friction between Ståle and the rest of the crew, which was really sad because Ståle and his credibility were the main reasons why Bataleon had been taken seriously by the snowboard industry to begin with.

Unfortunately, neither side could find it in them to reconcile the other’s wishes, leading Ståle —one of Norway’s most legendary shredders of all time— to walk away from Bataleon at the end of the season, determined to stay true to himself and his uncompromising vision. Ståle would drift around for a few years after leaving Bataleon before settling back in his native Dombås, focusing on a career as a guide and teacher at the local mountain school. With Ståle gone, that meant John would need to take on the role and lead the team, in addition to his other duties. He did, however, step down from graphic design, handing the baton off fully to Danny, who would be responsible for designing all the board graphics from here on out.

Despite losing someone as important to the company as Ståle, things were still moving forward in a positive manner. The right people in the industry were taking notice, and they were doing so for the all right reasons. When Lib Tech included all-new ‘Roll Bottom’ base technology —an obvious attempt at replicating Triple Base— on their Youth In Asia model that season, John and Danny swung by the Lib booth at SIA to check it out in person. Mike Olson and Pete Saari were there and recognized them, ‘whoa, it’s the Bataleon boys, what’s up dudes, keep up the great work’. Upon closer inspection, it was clear that Lib was following Bataleon’s lead, and it was a nice boost to the ego that these legends were recognizing the Triple Base concept was valid and worked.